The global pandemic known as coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) has claimed lives — including thousands across the United States — but, this health threat isn’t Pasco County’s first experience with uncertain times.

In fact, weeks after the county was formed by the Florida Legislature on June 2, 1887, it faced a deadly yellow fever.

At that time, Pasco had just one medical doctor, James G. Wallace, according to Bill Dayton, past president of the Dade City Historic Preservation Advisory Board.

The epidemic hit Florida’s port cities first, then spread to Tampa where five people died from yellow fever in September of 1886.

“It was reported that hundreds of people fled their homes, literally leaving meals on their tables,” Carol Jeffares Hedman wrote, in a history column published on Dec. 18, 2001, in The Tampa Tribune.

Dade City was still unincorporated and serving as a temporary county seat, when the Pasco County Commission adopted a countywide quarantine in 1887.

“There were no health departments back then,” said Glen Thompson, an environmental specialist who worked for the Pasco County Health Department from 1973 until 2006.

The Florida Southern Railroad had been transporting goods and products to Dade City since 1885. This new railroad also provided an opportunity to carry yellow fever into Pasco County.

“The Pasco County Commission voted to pay $5 per day to post guards at the Dade City Depot, among other points of entry,” Thompson explained.

With little knowledge of yellow fever, one popular theory suggested it traveled underground at 2 miles a day.

Experiments were tried, including one that involved firing military canons, on the premise that the shock waves could kill yellow fever.

John Wall, a physician and mayor of Tampa, from 1878 to 1880, was one of the first to point out that mosquitoes carried the disease.

Wall reported that in 1881 — 20 years before Walter Reed led a medical team in Central America and confirmed that fact in 1901.

Reed became famous for eliminating the threat of yellow fever for workers completing construction of the Panama Canal.

As for Wall, he contracted and survived yellow fever in 1871. He was still pleading his case when he died of a heart attack in 1895 while addressing the Florida Medical Association in Gainesville.

The Spanish influenza — the deadliest plague in history — claimed the lives of 100 million, worldwide, at the height of World War 1, according to “The Great Influenza,” a 2005 New York Times bestseller by author John Barry.

More people died from the Spanish influenza in that single year than the Black Death had killed in a century.

Local families were not spared from the suffering.

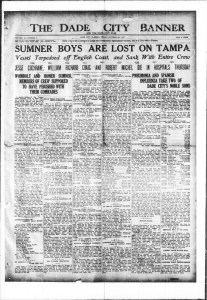

The first death from Spanish influenza reported by The Dade City Banner occurred in 1918.

It involved 21-year-old William Craig, a Dade City native, who was stationed in Camp Jackson, South Carolina.

The newspaper received a telegram reporting the death had occurred in the base camp’s hospital.

“Such was the sad cry that passed through Dade City this morning,” the newspaper later reported on its front page. “The family has requested that the body be shipped to Dade City.”

Churches closed, but The Dade City Banner reported on Oct. 25, 1918 that prayer services would be held on the courthouse lawn at 5 o’clock in the evening for divine intervention “…as a matter of precaution.”

Florida saw a total of 4,000 deaths in 1918 from Spanish influenza, and thousands more weakened survivors would die from pneumonia.

The Florida Legislature passed an act in 1931 to create county health departments using state funding, according to a historical account published in concert with the health department’s 75th anniversary.

But, it wasn’t until 1947 when the Pasco County Health Department first opened an office in Dade City.

Another Pasco County health challenge arose on Nov. 5, 1980, at what was then St. Leo College. It involved the outbreak of Norwalk Virus Gastroenteritis.

A 1985 report by the Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health said, in part, that: “College officials notified the local health department that more than 100 students complaining of sudden onset of abdominal cramps, vomiting, and diarrhea had reported to the Student Health Center since the previous evening.”

Former health department employee Thompson recalls: “We only had three health specialists on staff and were quickly overwhelmed with medical surveys and reports.”

Thompson joined a task force working with the Florida Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services and the Tampa Regional Laboratory to examine students and campus employees who had eaten one or more meals at the campus cafeteria from Nov. 3, 1980 to Nov. 5, 1980.

“The Norwalk virus was most likely spread by a combination of exposure to contaminated tossed salad and person-to-person transmission,” concluded the report submitted to the American Journal of Epidemiology. However, the report also noted, “the source of contamination was not identified.”

Now, the health department’s Pasco office is the midst of working to prevent the spread of COVID-19, while also continuing its work to address a Hepatitis A outbreak —an ongoing battle since 2016.

Pasco County led the state with 415 cases in 2019, followed by Pinellas County with 377 cases.

Since January 2019, there have been more than 3,200 cases in Florida associated with Hepatitis A. While this outbreak has not yet ended, Pasco showed new cases trending downward to nine so far in April 2020, according to Melissa Watts, public information officer with the Florida Department of Health in New Port Richey.

As of the morning of April 20, the number of positive COVID-19 cases in Pasco County, was 207, including three deaths.

Published April 22, 2020